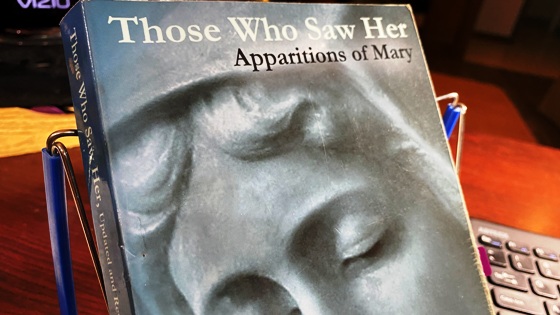

Those Who Saw Her, Catherine M. Odell… 2012년 한창 불타오르기 시작하던 신앙의 르네상스를 맞을 당시에 샀던 책… 그 중에서 현재 내가 필요한 부분을 다시 읽기 시작한다. 이 책은 가톨릭 교회의 공인을 받은 유명한 발현 스토리를 다루고 있지만 현재 관심사는 물론 Guadalupe 성모님 발현에 대한 것이다. 내년 달력에서 그것도 1월 말을 유심히 보며 예정된 Guadalupe 성지순례의 모습을 예상하며 상상을 한다. 과연 우리가 그곳, 인디언 모습으로 발현한 성모 마리아가 원주민 성 Juan Diego 앞에 나타나신 현장 Tepeyac 언덕엘 가볼 것인가? 예전에 큰 관심을 가지고 각종 성모발현에 대한 역사적 사실들을 읽고 보았지만 지금부터는 사실 Guadalupe에 관한 것만 공부해야 한다는 생각뿐이다. 어떻게 이번 성지 순례를 최대한 효과적으로 할 것인가, 지금부터 서서히 흥분이 되는 것이다. 최선을 다해서 이 신비중의 신비, 과달루페 성모님 발현에 대해서 공부하고 묵상을 하며 그때를 기다릴 것이다.

The Apparitions at Guadalupe, Mexico, 1531

Excerpt from Chapter 4, ‘Those Who Saw Her‘

For fifty-seven years, Juan Diego had lived near the shore of Lake Texcoco in a village hugging Tlateloco, the Aztec capital. As he walked toward that city on a chilly morning in 1531, his thoughts returned to the years of Aztec pagan rites and despicable human sacrifice. Later, the Spanish conquistadors had overwhelmed the Aztec chieftains, who had ruthlessly ruled the Indian tribes. For Juan and fifteen million Indians, a new time and spirit then began in his homeland.

In Juan’s own mind, only the last six of his years had been truly joyful. In 1525, he and his wife, Maria Lucia, had been baptized as Christians Juan, a farm worker and mat maker, had given up his Aztec name – Cuauhtlatoatzin, a word that meant “eagle that talks.” On most days, well before dawn, Juan was somewhere on this road, headed to or from Mass. His village was called Tolpetlac, near Cuauhtitlan. This day, December 9, 1531, was a Saturday, a day on which a special Mass was said in honor of the Virgin Mary.

For some time, his early morning walks had been solitary as he crossed the hill of Tepeyac and the Tepeyac causeway to Tlatelolco, the future Mexico City. Juan’s wife had died. There was only his uncle, Juan Bernardino. Juan Diego thought of his dead Maria Lucia many times as he made his way. There had been no children, and she had been precious to him.

As Juan approached the crest of Tepeyac Hill, he saw a cloud encircled with a rainbow of colors. Then he heard strange music coming from the hill as well. Could it be from some sort of rare bird? He wondered and stared up at the hill with the sun now rising behind it. A woman’s voice was calling above the music. He was fascinated but confused.

“Juanito Juan Dieguito…” the voice came, urging him. Since it seemed to be coming from behind the top of the hill, he ascended to the crest to look. A young woman, strikingly beautiful, stood there, beckoning him. She radiated such light and joy that Juan Diego could think of nothing more to do than drop to his knees and smile at her.

Everything around her seemed to catch the sweet fire she glowed with. The leaves of the plants surrounding her on the hill were aglow; the branches of the trees and bushes shone like polished gold. Around the whole hill, a rainbow of multicolored light seemed to have descended.

“Juanito [Little John], my sweet child, where are you going?” the woman asked him in Nahuatl, his own tongue.

“My Lady and my child,” he replied, in an Indian idiom of endearment, “I am on my way to the church at Tlatelolco to hear Mass.”

Then, with no further introduction, the shining young woman spoke very seriously and yet lovingly to Juan Diego. He listened with intensity born of instant devotion. The woman was so beautiful, so gracious. He could not ignore any request from her:

You must know and be very certain in your heart, my son, that I am truly the perpetual and perfect Virgin Mary, holy Mother of the True God through whom everything lives, the Creator and Master of Heaven and Earth.

I wish and intensely desire that in this place my sanctuary be erected so that in it I may show and make known and give all my love, my compassion, my help, and my protection to the people. I am your merciful Mother, the Mother of all of you who live united in this land, and of all mankind, of all those who love me, of those who cry to me, of those who seek me, of those who have confidence in me. Here I will hear their weeping, and sorrow, and will remedy and alleviate their suffering, necessities, and misfortunes.

And so that my intentions may be made known, you must go to the house of the bishop of Mexico and tell him that I sent you and that it is my desire to have a sanctuary built here.

Overwhelmed at knowing the identify of the woman, Juan then bowed in obedience to her request. Immediately, without turning back, he took leave of her and hurried toward the causeway into the city. He knew where to find the house of His Excellency Don Juan de Zumarraga, the recently named bishop of Mexico (New Spain).

In a little while, Juan was rapping on the door of the bishop’s house. It was still early morning, shortly after dawn. The bishop’s servants opened the door to him, with looks of scorn in their eyes: This Indian! Who is he to think of imposing on the lordly bishop, and at this hour! But Juan was eventually admitted into the bishop’s study.

With patience, the Spanish-born bishop listened as Juan told of his encounter with the Mother of God at the top of Tepeyac Hill. Juan’s excited account was translated from Nahuatl by one of the bishop’s aides. Bishop Zumarraga was respectful, but he did not really believe Juan. Tepeyac, the bishop had learned, was the site of the temple of the Aztec corn goddess, Tonantzin. Perhaps this simple Indian’s story was a jumble of that tradition and his newfound Christian beliefs.

The bishop told Juan Diego that he would think over what he had said. “Come back to see me in a few days,” he suggested.

Juan Diego could see that he had not convinced Bishop Zumarraga that what he said was true. The image of the Virgin was so sharply and beautifully impressed upon his own spirit. It was hard to believe that anyone else would deny her appearance or her wishes. Heavyhearted, he headed back to Tepeyac, thinking himself a failure.

As Juan climbed the rise to Tepeyac once again, the Lady was suddenly standing toward the top. He ran closer, dropped to his knees, and dropped his head as well. He was ashamed, but hoped that she would understand that he had tried. With deep regret, he told her of his attempt to convince Bishop Zumarraga. He talked about the bishop’s doubting eyes and puzzling smile. Juan feared that this man of God thought of him as a liar or a fool.

Burdened by his own helplessness, the quiet, good-hearted Indian broke down. Perhaps, he suggested, the Lady could find a more eloquent, more persuasive messenger.

If anything as Juan Diego later told it, his recitation of failures warmed her smile and her apparent affection for him. Her words were consoling. There were many messengers she could send, she admitted, but she had chosen him. In the ends, she promised, her requests would be answered through Juan’s efforts.

Courage and self-esteem once again flickered inside of him. Taking leave of “my Dear One, my Lady,” Juan made his way now to him home. On the following day, Sunday, December 10, he planned to visit the bishop’s house once again.

The next day was chilly, and Juan Diego made his way to Mass somewhat later than usual in the morning. His coarse cloak was needed, and he thanked the good God for it is he made his way to Mass. His spirit was at peace concerning the challenge after Mass. The Virgin told him that he would be the one to get her message across to the only man who could have a church built.

At the home of the bishop, Juan’s heart was once again thumping wildly with anxiety and fear. This time, Bishop Zumarraga listened more closely. His eyes did not wander all over the Indian’s face, looking for a sign of instability or a penchant for lying. He looked straight into Juan’s dark eyes as he spoke, with an aide interpreting. Still when Juan Diego was finished with his story – the same story as the day before – the bishop again refused to commit himself. He needed proof, he said.

“Perhaps you can bring me some sign of the Lady as a tangible proof that she is the Mother of God and that she definitely wants a temple built at Tepeyac Hill,” he said. Then Bishop Zumarraga smiled at Juan and left it at that.

Simply and humbly, Juan agreed. But the bishop was thoroughly surprised by the Indian’s consent to provide a miracle. As Juan left, Bishop Zumarraga sent two servants after him to track his movement. Outside of the city, the men from the bishop’s house lost sight of Juan Diego. He seemed to disappear into thin air, or into the sunset then settling over the land.

In fact, Juan Diego had again entered that special realm where his time and space were meshed with the Virgin’s on Tepeyac Hill. He agreed her and told her of the bishop’s request for proof. Gently, and with a smile, she assured Juan that there would be a sign on the following day. The bishop would have no more doubts.

If Juan was as happy as a man could be when descending the hill, the joy soon vanished. When he reached home, he found his uncle, his only relative, deathly ill. Juan Bernardino had soaring fever.

On the following day, Juan Diego could not leave his uncle’s side. He was frightened that the old man would die. There seemed to be no break in the fever’s grip. Juan’s spirit was heavy, and heavier still when he thought about his forsaken appointment with the bishop. When he thought of the beautiful Virgin Mother waiting for him to fulfill his promise, he was sick at heart. He almost wished that he, too, were on his deathbed.

Night brought no relief for Juan Bernardino. The sick man asked his nephew to leave early on the following morning for the monastery of Santiago Tlatelolco. He thought that death was near, and he wished to receive the anointing of the sick and the Eucharist.

Once Juan was on the road again, he began to fear meeting the Virgin. It was just before dawn on Tuesday, December 12. The day before, he was to have taken the verifying sign to the bishop for “his Dear One, his Lady.” How could he tell her that he had failed once again? The most direct route to the monastery would take him near Tepeyac and the shining Mother of God. He decided to take the long way around.

As he was skirting the hilltop where he had seen her before, Juan Diego was suddenly face-to-face again with the heavenly Lady. He shrank with embarrassment, but her greeting dispelled it.

“What troubles you, my dear son?” she asked. “Where are you going?”

Juan raised his eyes to her then and told her of the illness of his beloved uncle, Juan Bernardino. He had to care for him, he explained; there was no one else to do so. He begged her forgiveness for delaying the mission she had given him. The Blessed Virgin Mary’s response was reassuring:

Listen and be sure, my dear son, that I will protect you;; do not be frightened or grieved or let your heart be dismayed, however great the illness may be that you speak of. Am I not here, I who am your Mother, and is not my help a refuge? Am I not of your kind? Do not be concerned about your uncle’s illness, for he is not going to die. Be assured, he is already well. Is there anything else that you need?

With these words, the world of Juan Diego was once again washed with the clear, bright light of hope. Whatever the Virgin had said would surely come to pass. He listened as she gave him instructions about carrying the providential sign to Bishop Zumarraga. He would carry a bouquet of roses, Castilian roses, miraculously flowering on the Tepeyac, on a barren hill in winter. These he was to take to the bishop.

The Virgin directed him to climb to the top of Tepeyac Hill. He was to pick the roses now growing there where only cactus, thistles, and thornbush had previously been seen. Juan’s eyes grew wide at the lush abundance of roses of every color. He began to pluck them in great bunches and carry them back down to the Virgin. She arranged them in his tilma.

When it was heavy with the fragrant and radiant roses – heaven’s own hybrids – Juan carefully put the folded cloak over his head once again. He tied one corner to the top of the tilma at his shoulder to keep the flowers from tumbling out. Then, with a loving smile and farewell to the Lady, he was off again to the bishop’s residence. Talk to no one but the bishop, the Virgin had warned Juan. It was the last of four apparitions of the Blessed Virgin to Juan Diego at Guadalupe. He did not realize it as he left her, but Juan would only see the Virgin again in the image she had left behind.

At the home of Bishop Zumarraga, Juan Diego was admitted for the third time in four days. There was no scorn on the faces of the bishop’s servant this time. With open curiosity, they tried to see what he was carrying in the fold of his tilma. But Juan only held the ends of the garment closer to his chest, pushing the curious back. The roses were not to be crushed!

When he was in the presence of Bishop Zumarraga this time, Juan bubbled with his message. The Bishop stared at the tilma Juan was clutching. He listened as his interpreter struggled to keep up with the unbroken litany of Nahuatle chatter. Juan Diego shared the whole story about his uncle’s sickness and his inability to come the day before, about the day’s encounter with the Virgin once again, and about her insistence that a church be built on Tepeyac Hill.

Finally, Juan told of gathering the roses and of the way the Holy Mother arranged them with care in his cloak. With a smile of the purest joy, Juan then dramatically let loose the bottom of his tilma. The roses would fall to the floor in a rainbow cascade of glory at the bishop’s feet…or so Juan thought.

The bishop did watch as several roses fell to his carpet, but then his eyes moved back up to the tilma and filled with tears.

He fell speechless to his knees before Juan, who was still wearing the cloak, and began to beg pardon of the Virgin. There on the rough cactus-fiber tilma was an exquisite full-length portrait of the Virgin Mother of God, just as Juan had described her.

Now Juan Diego himself looked down at the front of his much-used cloak. Below him was a rendering of the heavenly woman he had so recently seen bending and arranging the roses in his cloak. She had been attired in a dark turquoise mantle, just like the figure in his portrait emblazoned on his old tilma.

A pink robe also adorned the image, just as the Lady had looked on Tepeyac. Her dark black hair could be seen beneath the mantle. Her posture was an attitude of humility and prayer, with her small, delicate hands joined, her head bowed to the left, her dark eyes half-shaded by the eyelids. Her eyes seemed patient, submissive. The facial features of the Virgin were delicate and beautiful, Indian in character but universal in appeal.

By now, Juan’s heart was in his throat, choking him with joy and tears. He started to life the cloak up over his head, and the bishop quickly rose from his knees to help him with the treasure. After some hesitation, Bishop Zumarraga carried it respectfully to his chapel and laid it before the Blessed Sacrament. By now, his entire household and a number of priests were also gathered around the miraculous portrait. Prayers rose in the chapel as groups of twos and threes spontaneously approached the tilma to kiss the bottom of it.

On December 13, the following day, Juan, who had stayed with the bishop overnight, began the trek back to Tepeyac Hill. This time his journey trailed a retinue of believers and the curious. Bishop Zumarraga asked the visionary to take him to see the place where Our Lady had literally touched New Spain.

Following this, Juan Diego hurried to his home. He had told the bishop about his uncle’s illness, but believed, as the Lady had promised, that he would find him well. Juan Bernardino was well. In fact, he was fully recovered and told his nephew that the Virgin had visited him, too:

I, too, have seen her. She came to me in this very house and spoke to me. She told me that she wanted a temple to be built at Tepeyac Hill. She said that her image should be called “Holy Mary of Guadalupe,” though she did not explain why.

In the bishop’s house, Juan de Zumarraga, a man who had left a Franciscan priory to come to this new land, was stirred to his depths. Our Lady of Guadalupe was known to the Spanish as an ancient statue depicting the divine motherhood of the Blessed Virgin.

Some questions were to continue throughout history concerning this name. Some authorities suggested that Zumarraga and the others heard a Nahuatl word, Coatalocpia (pronounced “Cuatlashupe”), which meant “Who crushed the Stone Serpent.” The crescent moon, beneath the feet of the Virgin on Juan Diego’s cloak, was symbolic of the serpent god. It brought to mind the pagan emblem of their Aztec religion, which had demanded human sacrifice.

In compliance with the wishes of the Virgin, Bishop Zumarraga planned to have a hermita, a little chapel or church, built there by Christmans. In the next two weeks, Indians flocked to Tepeyac Hill to erect the shelter for their Lady. On December 26, 1531, the day after Christmas and precisely two weeks after the miraculous image appeared, a procession was held. With great pomp, the cloak fo Juan Diego was carried from the bishop’s church to the chapel.

Accounts of the procession say that the Indians of the region had strewn the four-mile route with herbs and flowers. Dressed in bright costumes and adorned with feathers, hundreds danced as the image was borne past. But a near-tragedy along the way spread the devotion of Our Lady of Guadalupe even farther.

As part of the celebration, the Indians reenacted a mock battle by the lake near Tepeyac Hill. In the excitement, one of the Indians was accidentally pierced with an arrow in the neck. He died near the feet of the bishop and others who were escorting the precious tilma.

With grief, but with faith, too, he was picked up and placed in front of the mounted image of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Within moments, the “dead” man sat up. The arrow was carefully withdrawn, with no apparent damage except for a scar where the arrow had entered. The crowd on Tepeyac Hill went wild with joy. Both Spaniards and Aztecs – the latter having been recently released from the horror of a pagan cult – now discovered a living Mother who cared for her children.

To say that the life of Juan Diego was never the same is to state the obvious. He gave the cornfields and the small house that he owned to Juan Bernardino. A small hut was then built for the visionary on Tepeyac Hill. He acted as sacristan at the hermita (chapel), telling and retelling the story of the apparitions, the blessed tilma, and the wonders.

Bishop Zumarraga granted Juan the permission to receive the Eucharist at Mass three times a week, an unusual concession in that century. Juan made us of it but never with any sense of superiority or prestige. A major interrogation of natives of the area in 1666 revealed that, in those years following the apparitions, Juan was called “The Pilgrim.” Villagers living near Tepeyac recalled that their grandparents or great-grandparents often saw Juan making his way to Mass. He was always alone always aglow with a special peace and joy.

In 1548, Juan Diego and Bishop Zumarraga died within a few days of each other. Juan was seventy-four; Bishop Zumarraga died at seventy-two. In the decade following the apparitions and the creation of the Guadalupe image, either million Indians were baptized, and the growth of Christian conversion and devotion continued throughout the century.

The image of “Holy Mary of Guadalupe” has its mysteries for each century and culture to solve. In the century of its origin, the sixteenth, the picture of the Virgin functioned as a sort of graphic catechism for the Indian culture. In writing, the Aztecs used a form of picture writing, which was similar to Egyptian hieroglyphics used thousands of years earlier.

Here was a beautiful Aztec maiden. She stood in a posture that suggested peace or prayer. When the Indians viewed the portrait as a whole, they could see and “read” that this new maiden was more powerful than any and all of their pagan gods. And she did not demand their blood or the blood of their children. Instead, as they later learned, this mother’s kindness and care for them seemed never ending. The body and blood of the maiden’s Son, the Eucharist, would sustain them. The Mother of Jesus would also be their Mother and Protector.

Added to all this, the Indians could see that the Lady wore a brooch or pin at her throat with a black cross on it. This was the symbol used by the Franciscan friars who had come with the conquistadors early in the century. She was of heaven, and represented heaven’s power.

In 1709, a massive basilica was erected at the base of the hill to house the revered image on Juan Diego’s cloak. For over two centuries, it drew pilgrims from Mexico and all over the world. In 1921, a bomb hidden in a bouquet of flowers was placed on the altar just beneath the Guadalupe image. (Since 1971, the national constitution had fostered the intensely anti-Catholic rule in Mexico.) The bomb went off during Mass and shattered parts of the altar. However, no one attending Mass in the Guadalupe basilica was touched and the tilma, too, was unharmed.

In 1976, a new Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe was dedicated in Mexico City, while the older one was left standing on ground said to be sinking. An estimated fifteen million people visit Guadalupe each year. Processions still bring thousands on their knees to the feet of the Virgin.

In a different way, scientists of the twentieth century also have had to bow to the image.

Dr. Philip S. Callahan, an infrared specialist, biophysicist, and entomologist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Gainsville, Florida, studied the Guadalupe image in the spring of 1979. His work was done on behalf of the “Image of Guadalupe Research Project.”

After 448 years, the rough fabric on which the image was imprinted was still in fine condition. Essentially, the fabric could be compared to gunnysacking, Callahan said. The pigments that created the image, the researchers discovered, were similar to earth pigments that would have been in use during Juan Diego’s lifetime. Their color and quality were still rich, while the painted embellishments added in later decades had begun to fade and crack.

There had been no sizing or preparatory paint laid upon the surface of the fabric. There was no hint of preliminary sketching lines underneath – a shock to those who claimed that the painting was made by human hands. But on close inspection, the golden sunrays, stars, gold trim on the mantle, the moon, and the angel were found to be human “embellishments.” They were added to the original portrait of the Virgin over the centuries. All these additions to the image – sunburst, crescent moon, etc. – were found to be deteriorating, while the original portrait showed no sing of wear, tear, or fading.

Another remarkable discovery related to the tilma was found in the eyes of the Virgin. Greatly enlarged photos of the eyes revealed a human figure resembling Juan Diego. Though this finding might be dismissed as an illusion, the tilma itself cannot be.

The Guadalupe tilma is an object that the most rigorous examinations of modern science can’t explain. There is a great mystery in the rough cactus-fiber cloak that an Indian wore across his back on a December day many centuries ago. The tilma and its history have also been a great source of pride for the Mexican people. Seeing the fervor of pilgrims, Pope John Paul II remarked: “Ninety-five percent of the Mexican people are Catholics, but ninety-eight percent are Guadalupeans.”

The apparitions of Our Lady of Guadalupe were never officially confirmed as “worthy of belief in the same way that other apparitions were in later centuries. Perhaps the life-sized image miraculously produced on the tilma of Juan Diego made that unnecessary. In 1754, however, Pope Benedict XIV authorized a Mass and Office under the title of Our Lady of Guadalupe for celebration on December 12, her feast day. Also, Mary was named patroness of New Spain (Mexico), and in 1910, Our Lady of Guadalupe was named patroness of Latin America. Pope Pius XII proclaimed the patronage of the Guadalupe Madonna over both continents (North and South America) in 1945.

In 1990, Pope John Paul beatified Juan Diego, the visionary of Guadalupe. The celebration of Juan’s wonderful life and holiness was to be remembered as an optional feast on December 9. Then, a dozen years later, on July 31, 2002, the ailing Pope John Paul II traveled to Mexico City to canonize the visionary of the Guadalupe apparitions. Raising the humble Juan Diego to the altar of sainthood was a deeply touching event for his pope. After so many centuries, the people of Mexico could take pride in the fact that their own Juan Diego, the “talking eagle,” was finally a saint of the Church. His feast day in December 9, and the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe is celebrated on December 12.